One of the most famous hamlets in England is not generally remembered for its beauty nor the six-year guerrilla war waged by its inhabitants to try to stop their homes and land from being seized.

Juniper Hill sprang to fame in 1939 when Flora Thomson introduced the world to her isolated childhood community and the paupers who had lived there in the 1880s.

Thompson called the hamlet Lark Rise, painting an endearing and enduring portrait of the lives of agricultural labourers and their families living on the edge of poverty in 34 tiny cottages with no running water or sanitation and little knowledge of the wider world.

Juniper Hill sprang to fame in 1939 when Flora Thomson introduced the world to her isolated childhood community and the paupers who had lived there in the 1880s.

Thompson called the hamlet Lark Rise, painting an endearing and enduring portrait of the lives of agricultural labourers and their families living on the edge of poverty in 34 tiny cottages with no running water or sanitation and little knowledge of the wider world.

The book was adapted into a play and some of the characters featured in 40 episodes of a television series between 2008 and 2011.

One of the more memorable characters was Old Sally who could just remember when a few houses stood in a ring round an open green and her father had enjoyed commoner’s rights.

And while millions are familiar with the characters many will not realise that several of the men living there in the 1880s had taken part in a six-year battle some 30 years earlier to try to retain their customary and legal access to the common on which they lived and grazed their livestock.

One of the more memorable characters was Old Sally who could just remember when a few houses stood in a ring round an open green and her father had enjoyed commoner’s rights.

And while millions are familiar with the characters many will not realise that several of the men living there in the 1880s had taken part in a six-year battle some 30 years earlier to try to retain their customary and legal access to the common on which they lived and grazed their livestock.

It was a battle between peasants and the nobility running Eton Collage and nearby Tusmore Park Estate which had failed in attempts since 1761 to take control of the common - six square kilometres of heathland - under the Enclosure Acts.

Why would Eton College, 65 kilometres away, be involved? We need to travel back to feudal times when Cottisford Manor and its lands were owned by the Crown.

A year after founding Eton College in 1440 Henry VI gave the lands to the college as a source of income but the vast common of heathland remained a common.

Peasants living on or near commons had rights to pannage, turnery, piscary - putting animals and geese out to feed, taking turf or peat from the land to burn as fuel and fishing - as well as soil and mineral rights.

Thousands of acres of common land had been privatised since the first Inclosure Act of 1604 and in 1845 an Act of Parliament made it easier for commons and “waste lands” to be enclosed.

In 1847 Eton Collage and Tusmore Park applied for an order giving them the land to privatise, fence and farm. It was granted in February 1848.

But the peasants were determined not to give up their rights without a fight. Nearly 30 homes had been built by squatters in a grouping next to four freehold cottages, with each of those four having an acre of land, About 40 men were ready for battle.

GUERILLA WARS

Although newspapers were not available in Juniper Hill or the neighbouring village, news of violent resistance to an enclosure about 30 kilometres away would have become well known throughout the county.

Back in 1815 aristocrats had obtained an order to enclose Otmoor Common where for centuries peasants of seven villages around what was a vast marshland had enjoyed the right to graze their animals and geese.

The banks of a river flowing through the marsh were raised but this caused major flooding to farmers’ fields upstream. In 1829 aggrieved farmers destroyed the banks of the river and after months of organised destruction and disturbances, largely carried out anonymously at night, an army of about 1,000 villagers stormed the enclosed land on September 6 1830 in daylight hours. A headline in The Hereford Journal read: “The Military Attacked at Oxford and Sixty Prisoners Rescued”

The article read: “For some time past very serious disturbances have taken place at the seven Otmoor towns in this county, in consequence of the injury the farmers and others have sustained by the inclosure of an immense tract of commonable land. A great part of the population of the several towns assembled at different points, destroyed the fences, levelled the banks and mounds and filled up the ditches, and it is reported that the son of Sir A Croke, in resisting the rioters, has been severely wounded.”

Lord George Spencer-Churchill (Winston’s great grandfather) led a troop of yeomen cavalry to join the Oxford Militia to round up the mob’s leaders.

The newspaper reported: “About 60 of the rioters were brought to [Oxford] from Islip in wagons, guarded by infantry and a troop of horse. On passing through St Giles, where an immense number of persons had assembled to enjoy the festivities of a fair similar to St Bartholomew, the military were attacked in every direction; brick-bats, stones and bludgeons were hurled at them without mercy.”

After entering a narrow street on the way to the jail “…the yeomanry were forced one by one from their posts; and what afforded the mob no little amusement, the officer leading the troops was first to set off..” The prisoners were freed.

For more than four years villagers would go mob-handed to the moor on moonlit nights and destroy bridges, hedges and ditches despite soldiers being billeted in the area from time to time in an attempt to stop the destruction - which gradually petered out.

No doubt with this example in mind, the peasants of Juniper Hill did not wait for the common to be fenced and ditched before they took action to retain what had been common land for centuries.

“The process was violently resisted,” says historian Barbara English in a thoroughly-researched scholarly article published in 1985. “The notices were torn down from Cottisford church door, the surveyors were forced off the common and their instruments thrown aside; two magistrates and the superintending constable were similarly driven off; threats were issued by the squatters against anyone supporting the enclosure and there were interesting references to parallel Irish troubles.”

Newspapers reported how for six years “the Juniper Hill Mob” would not allow a spade to be put into the heath.

English says: “The magistrates suggested compromise, and appear to have been unwilling to force through the enclosure at all costs, perhaps remembering the violence that had accompanied the Otmoor enclosure…”

The parish constable at Cottisford was fined for opposing the enclosure. There was a threat to bring in soldiers. And court action resulted in some of the cottagers agreeing to a compromise.

The end came in 1853. On July 22 at Bicester Petty Sessions, held in a room at the King’s Arms in Market Square, 42 men from Juniper Hill stood before two judges from the local gentry charged that, being cottagers and occupiers of land at Juniper Hill, Cottisford, they were severally charged by William Kerr, the valuer of the enclosure of lands at Cottisford, with refusing to give up possession of certain lands there situated.

The Oxford Chronicle of July 30 reported that warrants were issued for ejectment.

Within days about 20 men armed with pickaxes and heavy tools arrived at the hamlet prepared to demolish the homes and “succeeded by these threats in forcing all the squatters to compromise,” according to English.

“The squatters were allowed to harvest that summer’s crops and were given 14-year leases of the nominal rent of five shillings a year; after that term the cottages would revert to the landowners.”

The enclosure commissioner had allowed the hamlet enough land for allotments and a playing field.

The men and their families who had been self sufficient were now forced to exist on the minimum agricultural labourer’s wage of 10 shillings a week by working in fields created on the land which had once been available to all commoners. And after 1867 they’d have to pay a weekly rent for the homes they had built.

The average workman’s wage in the early 1850s was about 16 shillings a week.

In Lark Rise Thompson tells how one of the cottagers was jailed for poaching - a reminder of the anonymous 17th century rhyme about enclosures:

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

LIFE IN LARK RISE IN THE 1880s

Flora Thompson was born in 1876 to a former children’s nurse and a stonemason. He set off each morning to spend the hours between 6am and 5pm working - and sometimes not coming home until he’d spent more than he should in the pub.

Why would Eton College, 65 kilometres away, be involved? We need to travel back to feudal times when Cottisford Manor and its lands were owned by the Crown.

A year after founding Eton College in 1440 Henry VI gave the lands to the college as a source of income but the vast common of heathland remained a common.

Peasants living on or near commons had rights to pannage, turnery, piscary - putting animals and geese out to feed, taking turf or peat from the land to burn as fuel and fishing - as well as soil and mineral rights.

Thousands of acres of common land had been privatised since the first Inclosure Act of 1604 and in 1845 an Act of Parliament made it easier for commons and “waste lands” to be enclosed.

In 1847 Eton Collage and Tusmore Park applied for an order giving them the land to privatise, fence and farm. It was granted in February 1848.

But the peasants were determined not to give up their rights without a fight. Nearly 30 homes had been built by squatters in a grouping next to four freehold cottages, with each of those four having an acre of land, About 40 men were ready for battle.

GUERILLA WARS

Although newspapers were not available in Juniper Hill or the neighbouring village, news of violent resistance to an enclosure about 30 kilometres away would have become well known throughout the county.

Back in 1815 aristocrats had obtained an order to enclose Otmoor Common where for centuries peasants of seven villages around what was a vast marshland had enjoyed the right to graze their animals and geese.

The banks of a river flowing through the marsh were raised but this caused major flooding to farmers’ fields upstream. In 1829 aggrieved farmers destroyed the banks of the river and after months of organised destruction and disturbances, largely carried out anonymously at night, an army of about 1,000 villagers stormed the enclosed land on September 6 1830 in daylight hours. A headline in The Hereford Journal read: “The Military Attacked at Oxford and Sixty Prisoners Rescued”

The article read: “For some time past very serious disturbances have taken place at the seven Otmoor towns in this county, in consequence of the injury the farmers and others have sustained by the inclosure of an immense tract of commonable land. A great part of the population of the several towns assembled at different points, destroyed the fences, levelled the banks and mounds and filled up the ditches, and it is reported that the son of Sir A Croke, in resisting the rioters, has been severely wounded.”

Lord George Spencer-Churchill (Winston’s great grandfather) led a troop of yeomen cavalry to join the Oxford Militia to round up the mob’s leaders.

The newspaper reported: “About 60 of the rioters were brought to [Oxford] from Islip in wagons, guarded by infantry and a troop of horse. On passing through St Giles, where an immense number of persons had assembled to enjoy the festivities of a fair similar to St Bartholomew, the military were attacked in every direction; brick-bats, stones and bludgeons were hurled at them without mercy.”

After entering a narrow street on the way to the jail “…the yeomanry were forced one by one from their posts; and what afforded the mob no little amusement, the officer leading the troops was first to set off..” The prisoners were freed.

For more than four years villagers would go mob-handed to the moor on moonlit nights and destroy bridges, hedges and ditches despite soldiers being billeted in the area from time to time in an attempt to stop the destruction - which gradually petered out.

No doubt with this example in mind, the peasants of Juniper Hill did not wait for the common to be fenced and ditched before they took action to retain what had been common land for centuries.

“The process was violently resisted,” says historian Barbara English in a thoroughly-researched scholarly article published in 1985. “The notices were torn down from Cottisford church door, the surveyors were forced off the common and their instruments thrown aside; two magistrates and the superintending constable were similarly driven off; threats were issued by the squatters against anyone supporting the enclosure and there were interesting references to parallel Irish troubles.”

Newspapers reported how for six years “the Juniper Hill Mob” would not allow a spade to be put into the heath.

English says: “The magistrates suggested compromise, and appear to have been unwilling to force through the enclosure at all costs, perhaps remembering the violence that had accompanied the Otmoor enclosure…”

The parish constable at Cottisford was fined for opposing the enclosure. There was a threat to bring in soldiers. And court action resulted in some of the cottagers agreeing to a compromise.

The end came in 1853. On July 22 at Bicester Petty Sessions, held in a room at the King’s Arms in Market Square, 42 men from Juniper Hill stood before two judges from the local gentry charged that, being cottagers and occupiers of land at Juniper Hill, Cottisford, they were severally charged by William Kerr, the valuer of the enclosure of lands at Cottisford, with refusing to give up possession of certain lands there situated.

The Oxford Chronicle of July 30 reported that warrants were issued for ejectment.

Within days about 20 men armed with pickaxes and heavy tools arrived at the hamlet prepared to demolish the homes and “succeeded by these threats in forcing all the squatters to compromise,” according to English.

“The squatters were allowed to harvest that summer’s crops and were given 14-year leases of the nominal rent of five shillings a year; after that term the cottages would revert to the landowners.”

The enclosure commissioner had allowed the hamlet enough land for allotments and a playing field.

The men and their families who had been self sufficient were now forced to exist on the minimum agricultural labourer’s wage of 10 shillings a week by working in fields created on the land which had once been available to all commoners. And after 1867 they’d have to pay a weekly rent for the homes they had built.

The average workman’s wage in the early 1850s was about 16 shillings a week.

In Lark Rise Thompson tells how one of the cottagers was jailed for poaching - a reminder of the anonymous 17th century rhyme about enclosures:

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

LIFE IN LARK RISE IN THE 1880s

Flora Thompson was born in 1876 to a former children’s nurse and a stonemason. He set off each morning to spend the hours between 6am and 5pm working - and sometimes not coming home until he’d spent more than he should in the pub.

Now a private house, in the 1880s this was the hamlet's pub - The Fox, renamed the Wagon and Horses by Thompson in Lark Rise.

It was a time when the older men still wore smock frocks with an “elaborately stitched yoke and snow white home laundering” in the fields. Boys wore petticoats to school until they were six or seven.

Flora was bathed regularly on Saturday nights. Water from a well was carried home on a yoke. Milk was a rare luxury. All the women over 50 took snuff. Toothbrushes were not in general use - some of the men used soot as a tooth powder Tomatoes - nicknamed love apples - appeared for the first time and chocolate was a recent arrival.

“There was no girl over 12 or 13 living permanently at home. Some were sent out to their first place at 11…the child was made to feel herself one too many in the overcrowded home, while her brothers when they left school and began to bring home a few shillings weekly, were treated with a new consideration and made much of.”

A few boys left the hamlet to become farm servants in the North of England. To obtain such situations, they went to Banbury Fair and stood in the market to be hired by an agent. They were engaged for a year and during that time were lodged and fed with the farmer’s family but received little or no money until the year was up when they were paid in a lump sum. At the hiring the different grades of farm workers stood in groups, according to their occupations.

As soon as cottagers got too old to work they had either to go to the workhouse, like Queenie who died in Bicester Workhouse aged 81, or split up to fit into the already overcrowded cottage of a child.

Christmas was a one-day holiday when children would be given an orange and a handful of nuts. There was no hanging of stockings apart from at the end house and the inn.

“In spring they ate the young green from the hawthorn hedges, which they called bread and cheese, and sorrel leaves from the wayside, which they called sour grass.”

Children would curtsey to the ladies passing by in a four-in-hand and boys would salute.

FORDLOW (COTTISFORD)

"A mile and a half away was the mother village of Fordlow - “a little, lost, lonely place much smaller than the hamlet, without a shop, an inn, or a post office.” But it did have a church and a school.

Cottisford Church, dating to the 13th century.

"The little squat church, without spire or tower, crouched back in a tiny churchyard that centuries of use had raised many feet above the road and the whole was surrounded by tall windy elms.”

Built in the 13th century, it is a small building with only a nave, chancel and south porch, which is Early English Gothic and has a sundial. The east window of the chancel dates from about 1300.

Below the steps down into the nave stood the harmonium, played by the clergyman’s daughter. A man played the violin “in one of the last instrumental church choirs”

Everybody might be equal in the eyes of God but the cottagers were placed at the back of the church.

With the help of Eton College a National school consisting of one large room was built in 1856 to accommodate 50 children. A two-roomed cottage adjoining it was built for the schoolmistress.

The school “was a small grey one-storied building standing at the cross-roads at the entrance to the village”.

Every morning at 10 o’clock the rector arrived to take the older children for scripture.

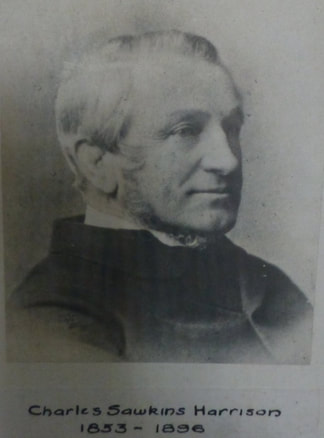

The Rev Charles Sawkins Harrison had arrived at the tiny village in 1853 and would have turned 70 in 1884.

He remained rector there until his death aged 81 in 1896. A history of the village records: “He restored the church and keenly supported the day school.”

Perhaps he had been born into the gentry when it was accepted that the eldest son inherited everything, the second and third sons went into the military and law, and younger sons entered the Church of England, helping it to be later labelled the Tory Party at prayer.

Thompson wrote: “Underlined in the church catechism was ‘To order myself lowly and reverently before my betters’.

“He was as far as possible removed by birth, education and worldly circumstances from the lambs of his flock…The children must not …be discontented or envious. God had placed them just where they were in the social order and given them their own special work to do; to envy others or to try to change their own lot in life was a sin of which he hoped they would never be guilty.”

Know your place - and sit at the back

OVER TO CANDLEFORD GREEN (FRINGFORD).

“The green, with its spreading oak with the white-painted seats, its roofed-in well, its church spire soaring out of trees, and its clusters of old cottages, was untouched by change.”

Miss Lane’s house was a long, low white one with the post office at one end and the blacksmith’s forge at the other. From her window at the post office she could see the twin red brick chimneys of the vicarage.

“The smiths, on account of the grubby, black nature of their

“The green, with its spreading oak with the white-painted seats, its roofed-in well, its church spire soaring out of trees, and its clusters of old cottages, was untouched by change.”

Miss Lane’s house was a long, low white one with the post office at one end and the blacksmith’s forge at the other. From her window at the post office she could see the twin red brick chimneys of the vicarage.

“The smiths, on account of the grubby, black nature of their

work, needed baths frequently, and for them, in the first place, the brew house had been turned into a bathroom. Wednesdays and Saturdays were their bath nights. Laura’s was Friday.”

Old Mr Stokes not only played the organ in the church (Candleford Green) but had built it.

THEN AS NOW

There’s a comment from a Conservative Party supporter about two ‘respectable’ men on their way to vote in a general election: “…as you may guess, they are voting for law and order.”

Children: “A few of the boldest among them were already beginning to talk about their right to live their lives as they wished…they seemed to think their parents existed chiefly to give them whatever they happened to wish for most at the moment.”

IN SEARCH OF LARK RISE

Literature and history buffs can find Hardy’s villages and towns in seven counties, Wordsworth’s Lake District is on every map of the UK and The Vanished World of H E Bates, just 60 kilometres to the north-east of Juniper Hill, is spread along Northamptonshire’s Nene Valley.

But you have to be very determined to find Lark Rise, still isolated today, just as it was in Thompson’s time.

The hamlet clings to the north-eastern edge of Oxfordshire a few hundred metres from the border with Northamptonshire.

There was no road to the hamlet when it was created, just a circular track linking the homes in the middle of the heath. But after the enclosure, in 1853, a lane was built connecting the main Oxford-Brackley road through the newly-created fields to existing lanes, It also nudged the edge of the hamlet’s track.

Driving north on the main road there is no turning into that lane. Turn back at the Barley Mow roundabout and with only 200 metres’ notice there’s a sign to Juniper Hill - single track road restricted to trucks under 7.5 tons.

Even with a map it’s possible when driving at the regulation 30mph to pass from boundary to boundary of the semi-den huddle of homes in less than 15 seconds without realising you’ve been there - and then finding the empty lane stretching on through gently undulating, hedged fields with not a home in sight.

Old Mr Stokes not only played the organ in the church (Candleford Green) but had built it.

THEN AS NOW

There’s a comment from a Conservative Party supporter about two ‘respectable’ men on their way to vote in a general election: “…as you may guess, they are voting for law and order.”

Children: “A few of the boldest among them were already beginning to talk about their right to live their lives as they wished…they seemed to think their parents existed chiefly to give them whatever they happened to wish for most at the moment.”

IN SEARCH OF LARK RISE

Literature and history buffs can find Hardy’s villages and towns in seven counties, Wordsworth’s Lake District is on every map of the UK and The Vanished World of H E Bates, just 60 kilometres to the north-east of Juniper Hill, is spread along Northamptonshire’s Nene Valley.

But you have to be very determined to find Lark Rise, still isolated today, just as it was in Thompson’s time.

The hamlet clings to the north-eastern edge of Oxfordshire a few hundred metres from the border with Northamptonshire.

There was no road to the hamlet when it was created, just a circular track linking the homes in the middle of the heath. But after the enclosure, in 1853, a lane was built connecting the main Oxford-Brackley road through the newly-created fields to existing lanes, It also nudged the edge of the hamlet’s track.

Driving north on the main road there is no turning into that lane. Turn back at the Barley Mow roundabout and with only 200 metres’ notice there’s a sign to Juniper Hill - single track road restricted to trucks under 7.5 tons.

Even with a map it’s possible when driving at the regulation 30mph to pass from boundary to boundary of the semi-den huddle of homes in less than 15 seconds without realising you’ve been there - and then finding the empty lane stretching on through gently undulating, hedged fields with not a home in sight.

Halfway through the hamlet and the open road is ahead.

In Thompson’s day the only clue to the existence of a modern world was the building of the Great Central Railway which passed about five kilometres east of the hamlet where “trains roared over a viaduct”. But it was an express line and no station was built anywhere near Juniper Hill, leaving the cottagers still cut off from the influence of the outside world.

The tracks were pulled up in the 1960s.

Today the only intrusion is on the skyline at the end of the lane beyond what the older people in the hamlet still referred to in Thompson’s time as the turnpike - the main road to Oxford which had become a toll road in the 18th century and which was so quiet “they could walk their mile along the turnpike and back without seeing anything on wheels”.

Rising above what is now called a trunk route, a near-motorway-standard dual carriageway, a gigantic white geodesic dome soars tens of metres above the tree line like a Brobdingnagian golf ball.

The American Air Force moved in to RAF Croughton (ironically, it has no runway) to build an ultra high tech centre which handles about a third of all U S military communications in Europe. But, once again, it has had no impact on the tiny hamlet.

The tracks were pulled up in the 1960s.

Today the only intrusion is on the skyline at the end of the lane beyond what the older people in the hamlet still referred to in Thompson’s time as the turnpike - the main road to Oxford which had become a toll road in the 18th century and which was so quiet “they could walk their mile along the turnpike and back without seeing anything on wheels”.

Rising above what is now called a trunk route, a near-motorway-standard dual carriageway, a gigantic white geodesic dome soars tens of metres above the tree line like a Brobdingnagian golf ball.

The American Air Force moved in to RAF Croughton (ironically, it has no runway) to build an ultra high tech centre which handles about a third of all U S military communications in Europe. But, once again, it has had no impact on the tiny hamlet.

The view across what would have been junipers on common heathland.

As Thompson explained, some of the cottages had two bedrooms, others only one. In nearly all of them here was but one room downstairs. So, over the years, extensions have been added to homes.

The rubble construction has resulted in some of the homes - Old Sally’s, for example - falling into disrepair and disappearing. A few new homes have been added but there are now only 21 houses in the hamlet.

But they are all in the same grouping and Thompson would almost certainly recognise her Lark Rise.

Unfortunately, the hamlet’s pub and social centre, The Fox, which appeared in the book as The Wagon and Horses, closed at the end of the last century and has become a private house.

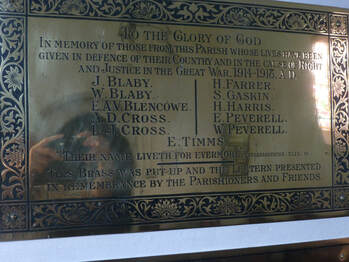

Thompson mentioned the lack of memorial tablets in Cottisford Church. There’s now one for Flora and another commemorating local men killed in the 1914-18 war, which tragically includes the name of her much-loved younger brother, Edwin Timms (Edmund in the book).

The rubble construction has resulted in some of the homes - Old Sally’s, for example - falling into disrepair and disappearing. A few new homes have been added but there are now only 21 houses in the hamlet.

But they are all in the same grouping and Thompson would almost certainly recognise her Lark Rise.

Unfortunately, the hamlet’s pub and social centre, The Fox, which appeared in the book as The Wagon and Horses, closed at the end of the last century and has become a private house.

Thompson mentioned the lack of memorial tablets in Cottisford Church. There’s now one for Flora and another commemorating local men killed in the 1914-18 war, which tragically includes the name of her much-loved younger brother, Edwin Timms (Edmund in the book).

It appears the rectory was auctioned, complete with furniture, carpets and feather beds, in 1896 after the Rev Harrison’s death. Like nine other churches in the area, the church no longer hIas an incumbent but the 10 are looked after by three clergy - all women.

Cottisford school and teacher’s house still stand at the crossroads.

The view from what was the Post Office where Thompson worked is no longer of the

Vicarage chimneys but of modern houses. And a curate now lives in a modern Fringford house.

THE END HOUSE …is now called Lark Rise Cottage.

In Flora’s time it comprised “two small thatched cottages made into one, with two bedrooms and a good garden”. It was built about 1820 from soft chalk rubble,

Its fame is such that the present owners, retired teachers Judith and Malcolm Harvey, are used to pilgrims arriving from as far away as Japan in obeisance to the characters and community immortalised in Lark Rise.

*Most people politely stay at the top of the drive, but start up a conversation if we are in the front garden,” Judith told me. “They are often invited in. People who think that because they have an interest in a literary figure, anything they do is OK, including walking round to the back garden and sitting down with us without warning, get short shrift.”

Those invited into the house see “a viciously-twisting oak staircase up to what may have originally been two small bedrooms but is now one and an en-suite. The ground floor was originally one room (now a sitting-room) and a lean-to scullery. In the 1950s the owners added a downstairs bedroom, then later people put on a proper kitchen and dining-room and we added a conservatory.”

In an article for a magazine she wrote: “We moved into a cabin in the garden in 2004 and lived there for four months whilst the old house was re-wired, re-plastered, re-plumbed … re-just about everything, but not ‘modernised’. The walls are 18 inches thick, we still have the original beams and staircase, and the upstairs bedroom still gets the warmth from the fire in the sitting-room.”

Judith and her husband were not Flora fans who were determined to move to Juniper Hill. They bought the cottage because it has an acre of land attached and for two years they had been trying to find somewhere with a large garden in the Bicester area

She had read the book as a child. He had spent two years teaching it for ‘O’ Level Eng. Lit. Both have become immersed in the community which continues to thrive despite the closure of the pub at the end of the last century.

Judith said: “Two modern annual events are Tea on the Field in July and a bonfire with food and sparklers in November. We have also held quizzes, coffee mornings, cheese and wine evenings and afternoon teas in residents’ homes and gardens. “We have raised money for charities, to buy equipment for events and to fund the use of a snowplough by a local farmer, so that we are not cut off in a bad winter.

She and Malcolm have held a lot of charitable events in the garden and she is involved in the poetry appreciation group and the reading group. She’s also the correspondent for the area church magazine.

Cottisford school and teacher’s house still stand at the crossroads.

The view from what was the Post Office where Thompson worked is no longer of the

Vicarage chimneys but of modern houses. And a curate now lives in a modern Fringford house.

THE END HOUSE …is now called Lark Rise Cottage.

In Flora’s time it comprised “two small thatched cottages made into one, with two bedrooms and a good garden”. It was built about 1820 from soft chalk rubble,

Its fame is such that the present owners, retired teachers Judith and Malcolm Harvey, are used to pilgrims arriving from as far away as Japan in obeisance to the characters and community immortalised in Lark Rise.

*Most people politely stay at the top of the drive, but start up a conversation if we are in the front garden,” Judith told me. “They are often invited in. People who think that because they have an interest in a literary figure, anything they do is OK, including walking round to the back garden and sitting down with us without warning, get short shrift.”

Those invited into the house see “a viciously-twisting oak staircase up to what may have originally been two small bedrooms but is now one and an en-suite. The ground floor was originally one room (now a sitting-room) and a lean-to scullery. In the 1950s the owners added a downstairs bedroom, then later people put on a proper kitchen and dining-room and we added a conservatory.”

In an article for a magazine she wrote: “We moved into a cabin in the garden in 2004 and lived there for four months whilst the old house was re-wired, re-plastered, re-plumbed … re-just about everything, but not ‘modernised’. The walls are 18 inches thick, we still have the original beams and staircase, and the upstairs bedroom still gets the warmth from the fire in the sitting-room.”

Judith and her husband were not Flora fans who were determined to move to Juniper Hill. They bought the cottage because it has an acre of land attached and for two years they had been trying to find somewhere with a large garden in the Bicester area

She had read the book as a child. He had spent two years teaching it for ‘O’ Level Eng. Lit. Both have become immersed in the community which continues to thrive despite the closure of the pub at the end of the last century.

Judith said: “Two modern annual events are Tea on the Field in July and a bonfire with food and sparklers in November. We have also held quizzes, coffee mornings, cheese and wine evenings and afternoon teas in residents’ homes and gardens. “We have raised money for charities, to buy equipment for events and to fund the use of a snowplough by a local farmer, so that we are not cut off in a bad winter.

She and Malcolm have held a lot of charitable events in the garden and she is involved in the poetry appreciation group and the reading group. She’s also the correspondent for the area church magazine.

The End House is now Lark Rise Cottage - people walk into the back garden and sit down without warning.

PRESERVING LARK RISE

For many more decades the hamlet will remain as unspoiled as it is today (although not being connected to a sewer network is probably not a plus). A conservation order was placed on it in 1980 so that “the special character and appearance can be identified and protected by ensuring that any future alteration preserves or enhances that identified special character.“

The local council re-examined the conservation order in 2009 and said” The hamlet is still evocative of the period in the 1880s of which she (Thompson) was writing and many of the buildings and routes she described remain today.

“Dramatisations by the BBC have recently created more awareness of the book and resulted in an increase in visitors. It is important that signage, measures to ensure residents’ privacy, erosion of grass verges and other changes that could occur as a result do not detract from the informal rural character of the area.”

The conservation order will ensure Juniper Hill will remain much as it is and was. There are still no street lights.

There are no descendants of the 1880s families living in the hamlet and none of the residents was born there.

But there is a remnant of the old common which gave its name to the community. There may no longer be a profusion of juniper shrubs - one of only three UK native species of conifer along with Scots pine and yew - but they remain in the gardens of the old pub and, fittingly, Lark Rise Cottage.

FURTHER READING:

Lark Rise to Candleford by Flora Thompson, Penguin Modern Classics

Judith Harvey’s magazine article:

"Lark Rise" and Juniper Hill: A Victorian Community in Literature and in History by Barbara English, Victorian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 7-34 (28 pages)

Published by Indiana University Press.

Juniper Hill Conservation Appraisal, Cherwell Council.

Delightful blog by “Rowan”: The Circle of the Year

The Otmoor enclosure

Cottisford Revisited, Ted and Joan Flaxman 2008.

The Real Lark Rise Parish, Ted and Joan Flaxman, 2009

https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/4861883.real-lark-rise/

Cottisford Church organ:

https://brcarlick.wordpress.com/2011/02/28/cottisford-church-organ/

NB In 1997 about 1,000 acres of Otmoor were acquired by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds which restored farmland to marshland

For many more decades the hamlet will remain as unspoiled as it is today (although not being connected to a sewer network is probably not a plus). A conservation order was placed on it in 1980 so that “the special character and appearance can be identified and protected by ensuring that any future alteration preserves or enhances that identified special character.“

The local council re-examined the conservation order in 2009 and said” The hamlet is still evocative of the period in the 1880s of which she (Thompson) was writing and many of the buildings and routes she described remain today.

“Dramatisations by the BBC have recently created more awareness of the book and resulted in an increase in visitors. It is important that signage, measures to ensure residents’ privacy, erosion of grass verges and other changes that could occur as a result do not detract from the informal rural character of the area.”

The conservation order will ensure Juniper Hill will remain much as it is and was. There are still no street lights.

There are no descendants of the 1880s families living in the hamlet and none of the residents was born there.

But there is a remnant of the old common which gave its name to the community. There may no longer be a profusion of juniper shrubs - one of only three UK native species of conifer along with Scots pine and yew - but they remain in the gardens of the old pub and, fittingly, Lark Rise Cottage.

FURTHER READING:

Lark Rise to Candleford by Flora Thompson, Penguin Modern Classics

Judith Harvey’s magazine article:

"Lark Rise" and Juniper Hill: A Victorian Community in Literature and in History by Barbara English, Victorian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 7-34 (28 pages)

Published by Indiana University Press.

Juniper Hill Conservation Appraisal, Cherwell Council.

Delightful blog by “Rowan”: The Circle of the Year

The Otmoor enclosure

Cottisford Revisited, Ted and Joan Flaxman 2008.

The Real Lark Rise Parish, Ted and Joan Flaxman, 2009

https://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/4861883.real-lark-rise/

Cottisford Church organ:

https://brcarlick.wordpress.com/2011/02/28/cottisford-church-organ/

NB In 1997 about 1,000 acres of Otmoor were acquired by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds which restored farmland to marshland

RSS Feed

RSS Feed